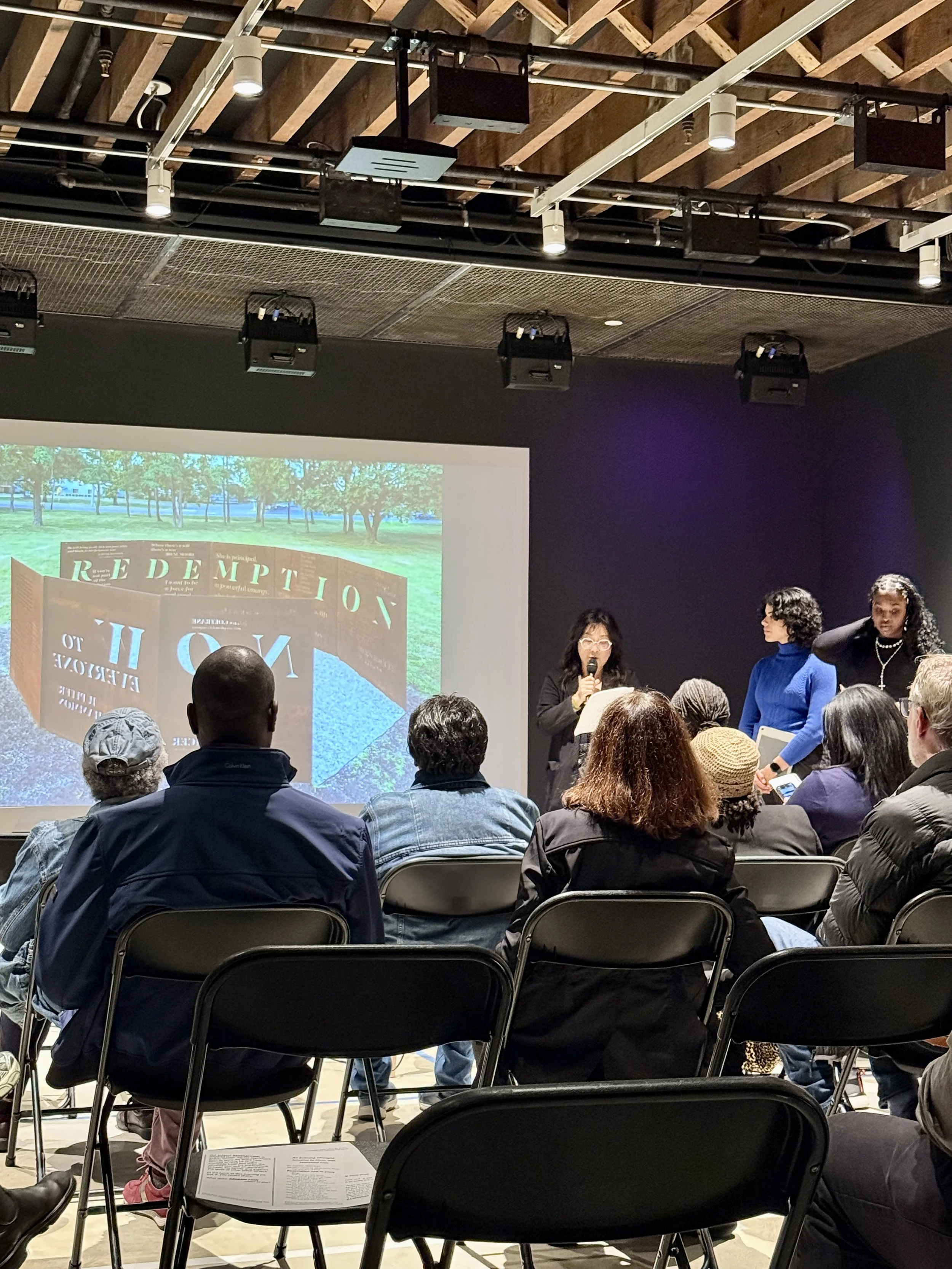

GRACE ONG YAN, principal of collective, presented “Redemption: Public Art for Community Voices” at New York’s Archtober festival at Williamsburg Biannual. She presented with Andrew Hart, co-principal, and students Polina Filipova, Leila Moutawakil, Anita Esin, and alumnus Elena Nestico. Sponsored by Community Design Collaborative, the event included an introduction by Irene Shum, co-founder and curator of Williamsburg Biannual, a presentation of the project by collective, and a panel discussion with Tya Winn, Executive Director of Community Design Collaborative, and Scott Ruff, Co-Executive Director of The Coles House Project and Adjunct Professor at Pratt Institute. A lively discussion ensued with Huntington community members in attendance. A prompt about what Redemption meant to the audience resulted in meaningful comments about hope and resilience in the current polarized climate. A special thank you to Williamsburg Biannual leadership— Jorge Zapata, Irene Shum, Goil Amornvivat, and Tom Morbitzer who generously provided us with a beautiful venue for the event.

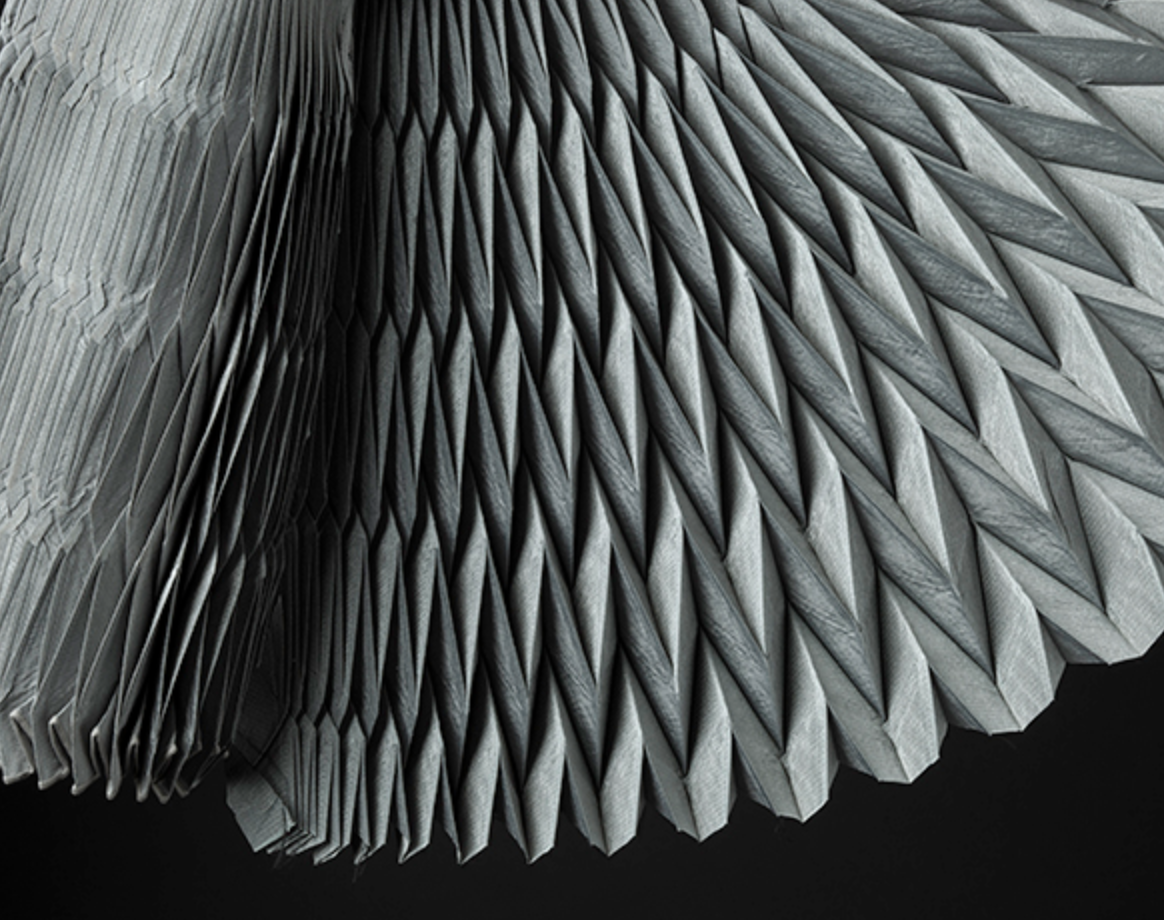

Reiko Sudo textile, Numo Manufacturing Corporation, 1991, from page 398 of David Raizman’s History of Modern Design

Decolonizing Design Histories CAA Session

Grace Ong Yan will be co-chairing the session, Decolonizing Modern Design, with Yelena McLane at the College Art Association Annual Conference on March 3, at 5:30pm EST.

Decolonizing Design Histories Session Description: First published in 2004, late professor and scholar David Raizman’s landmark interdisciplinary design history book, History of Modern Design, explored the dynamic relationship between design and manufacturing, and the technological, social, and commercial contexts in which this relationship developed. The book discussed many disciplines of design from typography to architecture, from seminal works to quotidian. Raizman contextualized design within “a framework that acknowledges a variety of perspectives through which it might be understood and appreciated, and that represent the dynamic interplay of multiple voices and forces within a given society and historical moment.” This inclusive approach is prescient today as we actively decolonize histories of modern design. Before his untimely passing, he was working on a third edition of this book. This session seeks papers that project and imagine the legacy of History of Modern Design and how race and gender shape diverse, equitable, and inclusive scholarship on modern design history. We are seeking papers that parse topics of modern design that build upon and depart from the chapter themes of his book: Art, Industry, and Utopias; Modernism and Mass Culture after World War II; Alternative Voices: Protest and Design.

The paper presentations are as follows: Reconsidering the Chaises Sandows: Materials, Makers, Industry, and Environments by Kiersten Thamm, University of Delaware; Chile: Design Strategies Against Neoliberalism by Rodrigo Alejandro Barreda, Interrogation by Design: Michael Pinsky’s Pollution Pods by Cynthia Haveson Veloric, University of the Arts, and “What should we do with design?” A reading of narratives in socialist Romania in the 1970s and the 1980s: the case of Decebal Scriba, by Mirela Duculescu, National University of Arts, Bucharest.

CAA 2022 Annual Conference Paper Presentation

Grace Ong Yan will be presenting her research at the 2022 College Art Association Annual Conference on March 5. Her paper is entitled “Designing Women: Avon Ladies, Entrepreneurship, and Constructing Media,” part of the session entitled Incorporating Design: Institutions, Markets, and Mediation in the History of Design, co-chaired by Anne Hilker and Colin Fanning. Ong Yan’s archival research was supported by a Hagley Exploratory Grant.

Paper Abstract: In contrast with the “organization men” of Trachtenberg’s The Incorporation of America, Avon Ladies engaged in an entrepreneurial capitalism. As a direct selling organization, Avon Products, Inc. eluded a male-dominated bureaucracy as well as fixed places of business, operating instead out of the commercialization of social relations. In this paper, I cast the Avon Lady as the entrepreneurial hinge between producers and consumers and shows how Avon constructed a mediated identity and presence in which design, gender, and race played a major role. My study spans the post-war era to the 1970s when throwaway culture, civil rights, and the feminine mystique collided. In this context, Avon choreographed production and consumption—feeding a desire for popular design in dialogue with changing attitudes in advertising and branding strategies to racially diverse audiences. For my presentation, I unpack materials from the Avon Products Inc. archives that engage design history, intersectionality, and business history, including intra-company marketing from sales booklets to prize contests as well as external advertising from product catalogs to ad campaigns. Also important are architectural designs of Avon labs and headquarters which conjured a de facto corporate culture for the far-flung reps. Viewed through a postmodern lens, I posit that Avon’s body of designs and business logistics comprised a necessary constructed reality for Avon Ladies and their customers. As a prescient model, Avon strategized and developed their identity virtually. Design was both conspicuous and absent, allowing for consumer participation within an alternative business structure.

Grace Ong Yan featured on Hagley podcast

Listen to Grace’s conversation on her latest book, Building Brands, with Ben Spohn in the Hagley History Hangout podcast.

Podcast featuring Grace Ong Yan on her new book

Grace Ong Yan was interviewed by Bryan Toepfer, host of New Books Network on her book, Building Brands: Corporations and Modern Architecture.

Grace Ong Yan presents paper at Docomomo_US National Symposium 2021

On May 28, Grace Ong Yan delivered her talk, "Signage at the Crossroads: Preserving Brand Identities" at the Docomomo_US 2021 National Symposium.

Abstract:

Twentieth-century modern architecture and design was the perfect vehicle for businesses to brand themselves as they constructed new identities through corporate headquarters. Over time, these buildings and in particular, their signs transcended branding to become landmarks and symbols for their communities. I will discuss how business and modern architecture intersected to create architectural branding that effectively spoke to the public with various case studies beginning with the 1932 PSFS Building by Howe and Lescaze. The preservation of branding focuses on the identity of the original clients who were important collaborators of the designs. Unfortunately, important urban-scaled signs are often removed and replaced with the new owner’s signs—a classic example of the baby being thrown out with the bathwater. This talk explores the issues, challenges, and triumphs of protecting and conserving these brand identities as important historical imprints that signal the crossroads of modern architecture and business clients.

Public Talk at The Skyscraper Museum

On May 11, 2021, Grace Ong Yan gave a virtual talk on her latest book at The Skyscraper Museum in New York. This lecture includes a Q&A with museum director, Carol Willis.

SAHGB features Building Brands →

The Society of Architectural Historians Great Britain featured Grace Ong Yan’s new book, Building Brands: Corporations and Modern Architecture on their website. The feature gives an overview of the book, as well as an excerpt about the fascinating case study of the 1964 “Plexiglas Palace” headquarters design by consulting architect Pietro Belluschi and associate architecture firm George M. Ewing and Co. for the Röhm and Haas company which invented and manufactured Plexiglas. This case study was the pinnacle of architectural branding as the building incorporated and displayed Plexiglas throughout, thus merging architecture and branding with brilliant designs and art of Plexiglas.

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia Book Talk →

For the public lecture series of the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, Grace Ong Yan discussed her book, Building Brands: Corporations and Modern Architecture, which examines how clients, architects, and designers together crafted buildings to reflect the company’s brand, carefully considering consumers’ perception and their emotions towards the architecture and the messages they communicated. As the first in-depth book to explore the role of branding in the design of corporate modernism, Building Brands re-tells the stories of four corporate headquarters in the context of both business and architectural histories: the PSFS Building by Howe and Lescaze, the Johnson Wax Building by Frank Lloyd Wright, Lever House by SOM, and The Röhm & Haas Building by Pietro Belluschi and George M. Ewing Co. In her illustrated talk, Grace Ong Yan explores the development of the branding concept in architecture- a much needed analysis of a widely used concept, thus providing a new perspective of architecture and design in mid-century American modernism.

"In Conversation" on Lund Humphries Blog →

Grace Ong Yan, author of the upcoming 'Building Brands: Corporations and Modern Architecture', talks to Meris Ryan-Goff about the inspirations for her book, the peculiarities of corporate architecture, and the keys to successful branding through buildings...

MRG: How did the idea for the book, Building Brands, first come about? And can you tell us about any surprising discoveries or particular challenges during the research process?

GOY: The topic of architectural branding grew out of an interest in how design and architecture engage people and shape human activities. I became involved with branding as a practicing architect and interior designer at Gensler New York. Together in an interdisciplinary team, we designed branded environments for companies like Toys R Us, International Center for Photography, and Bally. I was immediately fascinated by the practice of branding as an alternate lens of design. I found brand design to be in some ways more creative, interdisciplinary, and service-oriented than the world-renowned architecture firms that I had worked in previously. Architecture firms, especially those lead by famous architects, approach design as the development of a signature design. By comparison, I found that with brand design, the script was flipped—the process was not a realization of an architect’s vision, but about coming up with new design ideas to define the client's identity. This invigorating and very freeing experience left deep impressions on me. As I embarked on my doctoral studies in architectural history and theory with these insights, I felt I could offer a unique perspective.

The greatest challenge of researching corporations is accessing their archives as they generally do not welcome outside researchers. Yet this is what I needed to do in order to bring a new interdisciplinary lens to architectural history by seeking to answer my initial question: Did the clients seek advertising and branding through the architecture that they commissioned? For my research on how architecture served as branding, it was imperative to reveal the company’s motivations about the architecture it commissioned. I quickly discovered that the best way to research a company’s papers is to study defunct companies. When a company goes out of business or gets bought out by another company, its extant archival papers— inter-office memos, board meeting minutes, letters between clients and architects, annual reports, employee magazines, in short, all the documents it leaves behind, end up in a publicly accessible repository. What I unearthed from the abundant Philadelphia Saving Fund Society and Röhm and Haas archives were just such fine-grained documents that informed and supported my hunch that architecture in the form of corporate headquarters served their clients as far more than offices to house their employees, but as important promotional tools and as a communication medium to the public.